Since the intention of the DataStructureLess Competition was to showcase some interesting/unique solve techniques, I thought it would be good to provide some editorial for all of the problems so everyone can see some of the cool stuff on offer.

Each problem has been given a few hints, so you can hopefully have a stab at the solution even if you got stuck in contest, but a solution is also provided.

Binary 1

Hint 1

Simulating won’t be enough, because of the size of $i$. We need to somehow skip most of the previous values.

Hint 2

Note that the lengths of the binary numbers increase as we move along the sequence, in fact there are $2^k$ binary numbers of length $k+1$

Solution

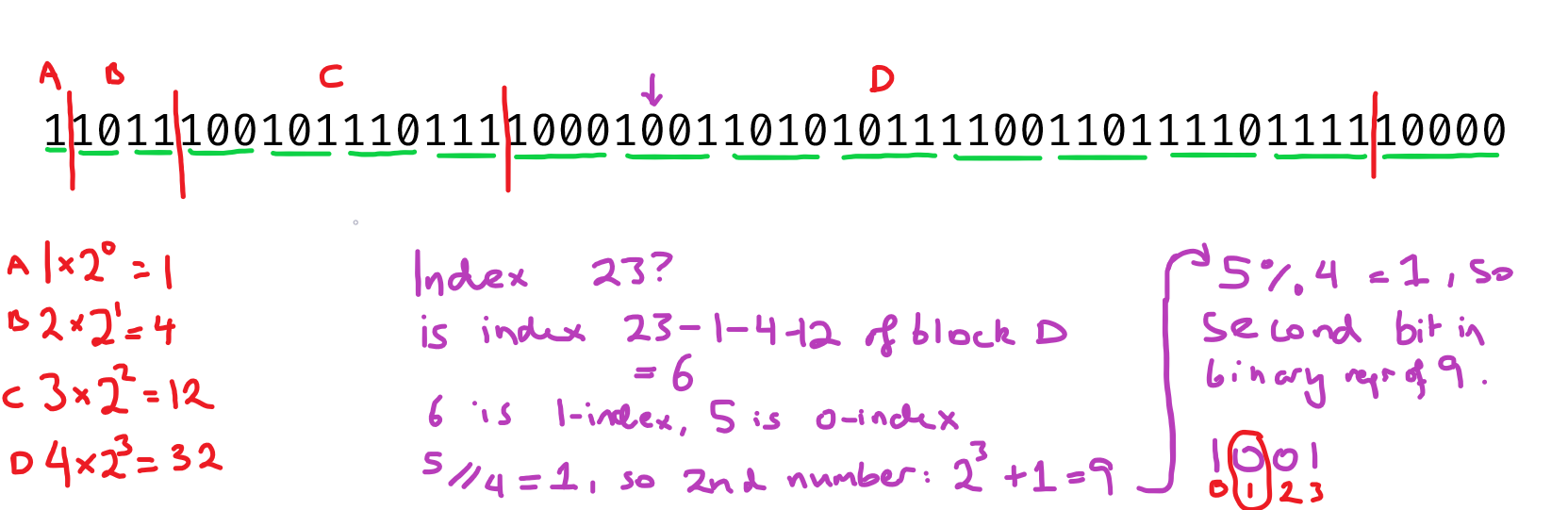

Assuming you’ve read the previous two hints, we want to skip ‘blocks’ of binary numbers of equal length. Since these blocks at least double in size each time we can get rid of an exponential amount of numbers before our index. We can continue subtracting these larger and larger blocks until our index would be exceeded by the next block: a jump of size $(k+1) * 2^k$, which tells us that the value we are trying to find is within a binary number of length $k+1$.

Now we know that after dealing with the first $p$ digits (Which contains all binary strings with less than $k+1$ length), we are left to find the $i-p^{th}$ value in the sequence of binary strings of length $k+1$. But since all binary strings are the same length now, we know we’re actually looking at the $\frac{i-p}{k+1}^{th}$ binary string in that sequence! From here we can just do some indexing to get what we need.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

index = int(input())

k = 0

# While our index is not in the next block of binary strings of length k+1

while index > (1 << k) * (k+1):

# Subtract our index to "offset" removing those binary strings

index -= (1 << k) * (k+1)

k += 1

bit_length = k+1

# 0 index, rather than 1-index.

index -= 1

# The jth binary string of length k+1 is 2^k + j (j is 0-indexed)

skip_num = index // bit_length

actual_num = (1 << k) + skip_num

# Now the remaining index is simply the index of our singular binary number

index = index % bit_length

print(bin(actual_num)[2:][index])

Complexity $\mathcal{O}(\log_2(n))$

Binary 2

Hint 1

If you’ve solved Binary 1, we need to make a similar revelation about jumps.

Hint 2

Notice that in blocks of binary strings of equal size, the first bit is always 1, and every other bit is equal parts 0 and 1.

Solution

As the hints note, since we cycle through every binary number in a block, the numbers 0 and 1 appear the same amount, except for the first bit of every number, which is always 1.

Therefore for a string of $2^k$ binary numbers of size $k+1$, they contain $k*2^{k-1} + 2^k$ 1s.

Once we’ve dealt with everything except our block, rather than iterating through the final block, we can make use of this fact for “subblocks”.

For example, if our final number starts with “11”, it means that all binary strings of length $k+1$ starting with “10” are also included, so the last $k-1$ bits in all these numbers have an equal amount of 0s and 1s. If instead our final number starts with “10”, then we can simply recurse down. This is a bit hard to express in code but hopefully the logic above is clear.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

36

37

38

39

40

41

42

43

44

45

46

47

48

49

50

51

52

53

54

55

56

57

58

59

60

61

62

63

64

import sys

index = int(input())

total_ones = 0

k = 0

bit_length = 1

while index > (1 << k) * (k+1):

index -= (1 << k) * (k+1)

if k == 0:

total_ones += 1

else:

# Same formula as $k*2^{k-1} + 2^k$

total_ones += (1 << (k - 1)) * (k + 2)

bit_length += 1

# We've counted all 1s in the prior blocks.

# 0 index.

index -= 1

# Our number has this bit_length.

skip_num = index // bit_length

actual_num = (1 << (bit_length-1)) + skip_num

def rec(prev_ones, min_val, max_val, power):

# Recursive function to count all 1s in our current block.

# prev_ones: 1s to the left of our current bit (IE, if we've got to our binary number starting with `1101`, then there are 3 previous 1s, which will always be 1s for future binary strings)

# min_val: The minimum value of the search block

# max_val: The maximum value of the search block

# ^ These two will squish together by powers of 2

# power: The power of 2 we are searching for next (decreases by 1 each time)

global total_ones

if power < 0:

return

print(f"{min_val} {max_val} jump {1 << power} ones {prev_ones}", file=sys.stderr)

# min_val is always a power of 2

# max_val is either a power of 2 or smaller (Since it starts as the actual number we are looking for).

if min_val + (1 << power) <= max_val:

# Our number has a `1` in the nth bit

# We can skip to the right half and count all the 1s in the left!

# First, add all the static 1s.

total_ones += (1 << power) * prev_ones

print(f"{(1 << power) * prev_ones} ones added from previous indicies", file=sys.stderr)

if power > 0:

# And also add the ones which occur with 50% frequency.

total_ones += (1 << (power-1)) * power

print(f"{(1 << (power-1)) * power} extra ones in the left half added", file=sys.stderr)

# recurse

rec(prev_ones+1, min_val + (1 << power), max_val, power-1)

else:

# Our number has a `0` in the nth bit

# We are in the left half

if power > 0:

rec(prev_ones, min_val, max_val, power-1)

print(f"Num lives in {actual_num}", file=sys.stderr)

rec(1, 1 << (bit_length-1), actual_num, bit_length-2)

index = index % bit_length

# rec doesn't count the final number.

total_ones += bin(actual_num)[2:][:index+1].count("1")

print(total_ones)

Complexity $\mathcal{O}(\log_2(n))$

Binary 3

Hint 1

Note that for even jump sizes, the answer is the same if we just divide the jump size by 2. So you can assume the jump size is odd.

Hint 2

While we don’t quite have the same nice rule about equal numbers of 1s and 0s, there is still some structure in our bits. For example, not (assuming odd jump size) that the least significant bit always toggles between 0 and 1. What happens to the second bit, the third?

Solution

The revelation here is that if we look at the first $2^k$ numbers in the sequence, the $k$ least significant bits actually do have an equal number of 0s and 1s! There are a few nice proofs of this, and I’ll leave it as a task for the reader to attempt (Hint: Note that if the jump size is odd, the jump size and $2^k$ are coprime).

So, we can continue some similar logic here to get rid of the first $k$ bits to deal with (and since we are dealing with a power of 2 as input, we don’t have to worry about our ‘current’ block).

Now all we need to do is worry about the extra bits we missed. Note that the jump size determines how many extra bits there are. In general, we should have $\log_2(j)$ extra bits to deal with. But this means that there’s at most $\approx j$ unique values for these extra bits, so we can simply find all of these values and add them up separately, by recursing in blocks of size $2^p$.

While you can solve this recursively, using the fact that the number of values divisible by $j$ in the range $(a, b]$ is $\lfloor \frac{b}{j} \rfloor - \lfloor \frac{a}{j} \rfloor$, as team de noted, you can also just use this formula between $[2^k\times a, 2^k\times (a+1))$ for every $a$ from 0 to $j$.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

36

37

38

39

40

41

import sys

from math import log2, floor, ceil

repeats, jump = list(map(int, input().split()))

# Make jump odd.

while jump % 2 == 0:

jump //= 2

total_ones = 0

# First, determine how many of the first k bits can be handled separately.

handled_bit_length = floor(log2(repeats))

# Handle the first handled_bit_length bits.

total_ones += (1 << (handled_bit_length - 1)) * handled_bit_length if handled_bit_length >= 1 else 0

print(f"Handled {total_ones} ones in the known block.", file=sys.stderr)

# Now we need to count the occurence of all bits after this in the sequence.

def rec(minval, maxval, cur_bit):

# rec checks for all 1s in cur_bit between minval and maxval.

global total_ones

# If cur_bit gets too small, we'll start double counting the bits we handled separately.

if cur_bit <= handled_bit_length - 1:

return

midway = minval + (1 << cur_bit)

if midway <= maxval:

# We have some space in the '1' of this cur_bit.

# Count how many numbers are within that are divisible by `jump`.

print(f"{maxval // jump - (midway-1) // jump} values in [{midway}, {maxval}], and all of these have a 1 in the {cur_bit}th bit.", file=sys.stderr)

total_ones += maxval // jump - (midway-1) // jump

# Recurse on the right branch

rec(midway, maxval, cur_bit-1)

# Recurse on the left branch

rec(minval, min(midway-1, maxval), cur_bit-1)

rec(0, repeats*jump, ceil(log2(repeats * jump)))

print(total_ones)

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

i,j = map(int, input().split())

while (j%2 == 0):

j //= 2

k = 0

iCopy = i

while iCopy > 1:

k += 1

iCopy//=2

s = [0]

for x in range(1,j+1):

s.append(x%2 + s[x//2])

# s[x] = # 1 bits in the binary representation of x.

tot = 0

for x in range(j + 1):

# count the occurences of s[x]*2^k up until s[x+1]*2^k.

tot += (min((i*(x+1)-1), i*j)//j - (i*x-1)//j)*s[x]

# Add the number of 1s in the least k significant bits

tot += k*i//2

print(tot)

Complexity $\mathcal{O}(\log_2(i) + j)$

Coins 1

This is a classic problem

Hint 1

The bounds imply a logarithmic solution. What’s the base of the logarithm?

Hint 2

Something akin to binary search would be good, although the binary search is optimal for a usual search because there are 2 equally possible outcomes for a query (value is left than or greater than the tester, equality means we stop immediately)

How many possible outcomes can the seesaw have? How can we use this to design a faster search?

Solution

The solution is to recognise that we want our query to break the solution space into three parts, depending on the seesaw result. We can do this by weighing one third of the remaining coins against another third. Then:

- If the left side is heavier, we need only recurse on that third of the coins

- If the right side is heavier, we need only recurse on that third of the coins

- If the left and right side are equal, then the fake coin must not have been weighed, so we recurse on the remaining third of the coins.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

def solve(coins):

if len(coins) == 1:

return coins[0]

if len(coins) == 2:

print(f"TEST {coins[0]} | {coins[1]}")

res = input()

if res == "LEFT":

return coins[0]

elif res == "RIGHT":

return coins[1]

else:

raise ValueError()

amount = len(coins) // 3

coin_left = coins[:amount]

coin_right = coins[amount:2*amount]

coin_extra = coins[2*amount:]

print(f"TEST {' '.join(map(str, coin_left))} | {' '.join(map(str, coin_right))}")

res = input()

if res == "LEFT":

return solve(coin_left)

elif res == "RIGHT":

return solve(coin_right)

elif res == "EQUAL":

return solve(coin_extra)

n = int(input())

coins = list(range(1, n+1))

print("ANS", solve(coins))

Complexity: $\mathcal{O}(\log_3(n))$

Coins 2

A similar idea for a problem, with some added intricacy - How do I recurse quickly to resolve where the 2 coins are?

Hint 1

Obviously since the setup is the same if we can place the 2 coins in separate piles, then we can simply apply the previous solution to solve within time.

So our solution needs to either:

- Recurse into a smaller problem with 2 fake coins

- Separate into two separate problems with a single fake coin each

Hint 2

We can’t quite immediately split into 3 evenly distributed problems because each seesaw option can feasibly be caused by two different configurations (For example, the left pile being bigger could be 2 in left, 0 elsewhere, or 1 in left and 1 unweighed).

Can we either:

- Change what we’re weighing so that this isn’t the case? or

- Provide additional weighing steps to disambiguate.

Solution

Following on from Hint 2, let’s follow these two options to two different solutions.

Option 1: Change what we query

Note that the fact that we have a third of the coins unweighed is the main cause of ambiguity. If there was a way to limit the size of the unweighed portion then our problems would mostly go away. So rather than splitting into thirds, lets do the original naive thing for coins 1, splitting in half, and only at most 1 coin will miss out from weighing. Then:

- If the seesaw goes LEFT, then all fake coins are in the left pile (or the additional unweighed)

- If the seesaw goes RIGHT, then all fake coins are in the right pile (or the additional unweighed)

- If the seesaw is EQUAL, then the additional coin cannot be fake. There must be a fake coin in each of the two weighed piles

This solution will have the maximum of $\log_2(n)$ and $2\log_3(n)$ queries ($2\log_3(n)$).

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

36

37

38

39

40

41

42

43

44

45

46

47

48

49

50

def solve_1(coins):

# log_3(n)

if len(coins) == 1:

return coins[0]

if len(coins) == 2:

print(f"TEST {coins[0]} | {coins[1]}")

res = input()

if res == "LEFT":

return coins[0]

elif res == "RIGHT":

return coins[1]

else:

raise ValueError()

amount = len(coins) // 3

coin_left = coins[:amount]

coin_right = coins[amount:2*amount]

coin_extra = coins[2*amount:]

print(f"TEST {' '.join(map(str, coin_left))} | {' '.join(map(str, coin_right))}")

res = input()

if res == "LEFT":

return solve_1(coin_left)

elif res == "RIGHT":

return solve_1(coin_right)

elif res == "EQUAL":

return solve_1(coin_extra)

def solve_2(coins):

# 2*log_3(n)

if len(coins) == 2:

return coins

amount = len(coins) // 2

coin_left = coins[:amount]

coin_right = coins[amount:2*amount]

coin_extra = coins[2*amount:]

print(f"TEST {' '.join(map(str, coin_left))} | {' '.join(map(str, coin_right))}")

res = input()

if res == "LEFT":

return solve_2(coin_left + coin_extra)

elif res == "RIGHT":

return solve_2(coin_right + coin_extra)

elif res == "EQUAL":

return solve_1(coin_left), solve_1(coin_right)

n = int(input())

coins = list(range(1, n+1))

print("ANS", *solve_2(coins))

Option 2: Add a clarifying additional query.

This solution is more complicated, where we instead add an additional query to resolve the initial result.

Let’s call the state x-y-z if there are x fake coins in the left pile, y in the right, and z in the remaining unweighed coins

- If the original query is LEFT, then this is either 2-0-0 or 1-0-1.

- We can add an additional query comparing one half of extra to the other half of extra

- If the second query is left or right, it is 1-0-1 and we can recurse

- If the second query is equal, then it is 2-0-0 (or the extra coins were odd and the remaining unweighed is fake), and we can recurse

- Same rule applies for RIGHT, either 0-2-0 or 0-1-1.

- If the original query is EQUAL, then this is either 1-1-0 or 0-0-2.

- We can resolve this by weighing all of the unweighed coins against a combination of left and right coins.

- If the second query says the LEFT, then the unweighed coins are heavier and we recurse on the unweighed coins

- If the second query says the RIGHT, then the left/right pile coins have a fake coin each

- If the second query says EQUAL, then the left/right pile coins we haven’t chosen are the ones that must have a fake coin each

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

36

37

38

39

40

41

42

43

44

45

46

47

48

49

50

51

52

53

54

55

56

57

58

59

60

61

62

63

64

65

66

67

68

69

70

71

72

73

74

75

76

77

78

79

80

81

82

83

84

85

86

87

88

89

90

91

92

93

94

95

96

97

98

99

100

101

102

103

104

105

106

107

108

109

110

111

112

113

114

115

116

117

118

119

120

121

122

123

124

125

126

127

def solve_1(coins):

# log_3(n)

if len(coins) == 1:

return coins[0]

if len(coins) == 2:

print(f"TEST {coins[0]} | {coins[1]}")

res = input()

if res == "LEFT":

return coins[0]

elif res == "RIGHT":

return coins[1]

else:

raise ValueError()

amount = len(coins) // 3

coin_left = coins[:amount]

coin_right = coins[amount:2*amount]

coin_extra = coins[2*amount:]

print(f"TEST {' '.join(map(str, coin_left))} | {' '.join(map(str, coin_right))}")

res = input()

if res == "LEFT":

return solve_1(coin_left)

elif res == "RIGHT":

return solve_1(coin_right)

elif res == "EQUAL":

return solve_1(coin_extra)

def solve_2(coins):

# 2*log_3(n)

if len(coins) == 2:

return coins

amount = len(coins) // 3

if 2 * amount < len(coins) - 2*amount:

# This essentially just deals with 5.

amount += 1

coin_left = coins[:amount]

coin_right = coins[amount:2*amount]

coin_extra = coins[2*amount:]

print(f"TEST {' '.join(map(str, coin_left))} | {' '.join(map(str, coin_right))}")

res = input()

if res == "LEFT":

# Either 2-0-0

# or 1-0-1.

# Check by comparing half of extra against itself.

# Some base cases for the second test:

if len(coin_left) == 1:

return solve_1(coin_left), solve_1(coin_extra)

if len(coin_extra) == 1:

print(f"TEST {coin_left[0]} | {coin_extra[0]}")

res2 = input()

if res2 == "LEFT":

return solve_2(coin_left)

elif res2 == "RIGHT":

return solve_1(coin_left[1:]), solve_1(coin_extra)

elif res2 == "EQUAL":

# Since coin_left == 2

return solve_1(coin_left[:1]), solve_1(coin_extra)

return None

# Now the meat and potatoes

extra_amount = len(coin_extra) // 2

extra_left = coin_extra[:extra_amount]

extra_right = coin_extra[extra_amount:2*extra_amount]

extra_extra = coin_extra[2*extra_amount:] # read all about it

print(f"TEST {' '.join(map(str, extra_left))} | {' '.join(map(str, extra_right))}")

res2 = input()

if res2 == "LEFT":

# 1-0-1-0

return solve_1(coin_left), solve_1(extra_left)

elif res2 == "RIGHT":

# 1-0-0-1

return solve_1(coin_left), solve_1(extra_right)

elif res2 == "EQUAL":

# 2-0-0-0 (plus extra_extra)

return solve_2(coin_left + extra_extra)

elif res == "RIGHT":

# Either 0-2-0

# or 0-1-1.

# Check by comparing half of extra against itself.

# Some base cases for the second test:

if len(coin_right) == 1:

return solve_1(coin_right), solve_1(coin_extra)

if len(coin_extra) == 1:

print(f"TEST {coin_right[0]} | {coin_extra[0]}")

res2 = input()

if res2 == "LEFT":

return solve_2(coin_right)

elif res2 == "RIGHT":

return solve_1(coin_right[1:]), solve_1(coin_extra)

elif res2 == "EQUAL":

# Since coin_right == 2

return solve_1(coin_right[:1]), solve_1(coin_extra)

return None

extra_amount = len(coin_extra) // 2

extra_left = coin_extra[:extra_amount]

extra_right = coin_extra[extra_amount:2*extra_amount]

extra_extra = coin_extra[2*extra_amount:] # read all about it

print(f"TEST {' '.join(map(str, extra_left))} | {' '.join(map(str, extra_right))}")

res2 = input()

if res2 == "LEFT":

# 0-1-1-0

return solve_1(coin_right), solve_1(extra_left)

elif res2 == "RIGHT":

# 0-1-0-1

return solve_1(coin_right), solve_1(extra_right)

elif res2 == "EQUAL":

# 0-2-0-0 (plus extra_extra)

return solve_2(coin_right + extra_extra)

elif res == "EQUAL":

# Either 1-1-0 or 0-0-2

# Resolve by weighing all of extra against some subset of left+right

not_extra = (coin_left + coin_right)[:len(coin_extra)]

print(f"TEST {' '.join(map(str, coin_extra))} | {' '.join(map(str, not_extra))}")

res2 = input()

if res2 == "LEFT":

# 0-0-2

return solve_2(coin_extra)

elif res2 == "RIGHT":

return solve_1(coin_left), solve_1(coin_right)

elif res2 == "EQUAL":

# only 1-1-0 is possible, when n=5,

return solve_1(coin_left), solve_1(coin_right)

n = int(input())

coins = list(range(1, n+1))

print("ANS", *solve_2(coins))

Complexity: $\mathcal{O}(2\log_3(n))$

Coins 3

The new style seesaw requires us to completely ignore past solutions and find 3 fake coins

Hint 1

The single coin version of the problem can be solved in $\mathcal{O}(\log_4(n))$ guesses.

The double coin version of the problem can be solved in $\mathcal{O}(\log_2(n))$ guesses.

Hint 2

If you’ve solved the previous two problems, this should really just be applying the same mantra - how can I make 1/2 guesses to completely disambiguate which pile of coins the fake coins lie in.

Solution

Let’s start off by coding in solve1 and solve2, as there isn’t much interesting to this:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

36

37

38

39

40

41

42

43

44

45

46

47

48

49

50

51

52

53

54

55

56

57

58

59

60

61

62

63

64

65

66

67

68

69

70

71

72

73

74

75

76

77

78

79

80

81

82

83

84

85

86

87

88

89

90

91

92

93

94

95

96

97

98

99

100

101

102

103

104

105

106

107

108

109

def guess(c1, c2, c3):

print("TEST", " ".join(map(str, c1)), "|", " ".join(map(str, c2)), "|", " ".join(map(str, c3)))

return [

list(map(int, section.strip().split()))

for section in input().split(">")

]

def solve_1(coins):

if len(coins) == 1:

return coins[0]

elif len(coins) == 2:

res = guess(coins[:1], coins[1:], [])

assert len(res) == 3

if res[0][0] == 1:

return coins[0]

else:

return coins[1]

amount = (len(coins) + 1) // 4

coin1 = coins[:amount]

coin2 = coins[amount:2*amount]

coin3 = coins[2*amount:3*amount]

coin4 = coins[3*amount:]

res = guess(coin1, coin2, coin3)

assert len(res) != 3

if len(res) == 2:

# The heavier one is alone.

if res[0][0] == 1:

return solve_1(coin1)

if res[0][0] == 2:

return solve_1(coin2)

if res[0][0] == 3:

return solve_1(coin3)

else:

# All are equal, the remainder is the culprit.

return solve_1(coin4)

def solve_2(coins):

if len(coins) == 2:

return coins[0], coins[1]

elif len(coins) == 3:

res = guess([coins[0]], [coins[1]], [coins[2]])

cur = []

if 1 in res[0]:

cur.append(coins[0])

if 2 in res[0]:

cur.append(coins[1])

if 3 in res[0]:

cur.append(coins[2])

return cur[0], cur[1]

elif len(coins) in [4, 5]:

res = guess([coins[0]], [coins[1]], [coins[2]])

assert len(res) != 3

if len(res) == 1:

return solve_2(coins[3:])

cur = []

if 1 in res[0]:

cur.append(coins[0])

if 2 in res[0]:

cur.append(coins[1])

if 3 in res[0]:

cur.append(coins[2])

if len(cur) == 1:

cur.append(solve_1(coins[3:]))

return cur[0], cur[1]

# At least 6, so 3*coin4 <= len

amount = (len(coins)+2) // 4

coin1 = coins[:amount]

coin2 = coins[amount:2*amount]

coin3 = coins[2*amount:3*amount]

coin4 = coins[3*amount:]

res = guess(coin1, coin2, coin3)

assert len(res) != 3 # 3 Distinct weights doesn't make sense with 2 coins

if len(res) == 2:

# There is an imbalance.

if len(res[0]) == 2:

# There are 2 heavy piles and 1 light pile

# 1-1-0

cur = []

if 1 in res[0]:

cur.append(solve_1(coin1))

if 2 in res[0]:

cur.append(solve_1(coin2))

if 3 in res[0]:

cur.append(solve_1(coin3))

return cur[0], cur[1]

else:

# There is 1 heavy pile and 2 light piles

# 2-0-0-0, or 1-0-0-1

if res[0][0] == 1:

weighted_first = coin1 + coin2 + coin3

elif res[0][0] == 2:

weighted_first = coin2 + coin3 + coin1

elif res[0][0] == 3:

weighted_first = coin3 + coin1 + coin2

weighted = weighted_first[:len(coin4)]

empty = weighted_first[len(coin4):2*len(coin4)]

res2 = guess(weighted, empty, coin4)

assert len(res2) == 2

if len(res2[0]) == 2:

return solve_1(weighted), solve_1(coin4)

else:

return solve_2(weighted)

else:

# 0-0-0-2

return solve_2(coin4)

Now, to solve the 3 coin case, let’s divide our coins into 3 piles of size $a$, plus the remainder.

Let’s do the case analysis for different outcomes of the weighing.

- If the outcome of the weighing has 3 distinct bands of weight (like

3 > 1 > 2), then we know the heaviest pile has 2 fake coins, and the middle pile has 1 fake coin.- Final complexity: $1 + \log_4(a) + \log_2(a) = 3\log_4(a)$

- If the outcome of the weighing has 2 distinct bands of weight, with two heavier piles (

3 1 > 2), then both heavy piles have 1 fake coin, and the remainder has 1 fake coin.- Final complexity: $1 + 2\log_4(a) + \log_4(n-3a)$

- If the outcome of the weighing has 2 distinct bands of weight, with two lighter piles (

3 > 1 2), then the heavy pile has anywhere from 1 to 3 fake coins, and the remainder has anywhere from 0 to 2 fake coins.- This can simply be solved by recursing to find 3 coins in the heavy pile plus the remainder in $1 + T(n-2a)$

- If the outcome of the weighing has 1 distinct band of weight (all equal), then either all piles have a fake coin, or the remainder has all 3 fake coins

- We can disambiguate this by weighing the entire remainder against a subset of the weighed piles, giving a complexity of $2 + \text{max}(3\log_4(a), T(n-3a))$

However, you’ll notice the remainder causes some issues in the final case, and our logic can be made much simpler if we just make each weighed pile about $n/3$ in size. Then in the final case, all 3 fake coins being in the remainder is impossible!

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

36

37

38

39

40

41

42

43

44

45

46

47

48

49

50

51

52

53

54

55

56

57

58

59

60

61

62

63

64

65

66

def solve_3(coins):

if len(coins) == 3:

return coins[0], coins[1], coins[2]

elif len(coins) == 4:

res = guess([coins[0]], [coins[1]], [coins[2]])

if len(res) == 1:

return coins[0], coins[1], coins[2]

else:

if 1 in res[1]:

return coins[1], coins[2], coins[3]

if 2 in res[1]:

return coins[0], coins[2], coins[3]

if 3 in res[1]:

return coins[0], coins[1], coins[3]

amount = len(coins) // 3

coin1 = coins[:amount]

coin2 = coins[amount:2*amount]

coin3 = coins[2*amount:3*amount]

coin4 = coins[3*amount:]

res = guess(coin1, coin2, coin3)

if len(res) == 3:

# 2-1-0-0

cur = []

if res[0][0] == 1:

cur.extend(solve_2(coin1))

if res[0][0] == 2:

cur.extend(solve_2(coin2))

if res[0][0] == 3:

cur.extend(solve_2(coin3))

if res[1][0] == 1:

cur.append(solve_1(coin1))

if res[1][0] == 2:

cur.append(solve_1(coin2))

if res[1][0] == 3:

cur.append(solve_1(coin3))

return cur[0], cur[1], cur[2]

elif len(res) == 2:

if len(res[0]) == 2:

# 1-1-0-1

cur = []

if 1 in res[0]:

cur.append(solve_1(coin1))

if 2 in res[0]:

cur.append(solve_1(coin2))

if 3 in res[0]:

cur.append(solve_1(coin3))

cur.append(solve_1(coin4))

return cur[0], cur[1], cur[2]

else:

# 3-0-0-0

# 2-0-0-1

# 1-0-0-2

cur = coin4

if res[0][0] == 1:

cur.extend(coin1)

if res[0][0] == 2:

cur.extend(coin2)

if res[0][0] == 3:

cur.extend(coin3)

# log_3(n)

return solve_3(cur)

else:

# 0-0-0-3 - not possible due to definition of amount.

# 1-1-1-0

return solve_1(coin1), solve_1(coin2), solve_1(coin3)

Complexity: $\mathcal{O}(3\log_4(n))$ guesses

Cutting Board 1

These next two problems invite you to think about optimal strategies in a game of cuts.

Hint 1

Try to classify some small games as one of the four outcomes, try to make some rules for combining 2 boards.

Hint 2

- Can the game ever have a strategy where the 1st player alyways wins?

- Is it just boards with length = width where the 2nd player alyways wins?

Solution

Let’s try to analyse the smallest few games, and in doing so make some rules for combining boards together.

We’ll call a game $2$ if the second player wins, $1$ if the first player wins, and $V$ or $H$ for Vaughn/Hazel winning always.

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | V | ||||||||

| 2 | H | |||||||||

| 3 | ||||||||||

| 4 | ||||||||||

| 5 | ||||||||||

| 6 | ||||||||||

| 7 | ||||||||||

| 8 | ||||||||||

| 9 | ||||||||||

| 10 |

The $1\times 1$ game is super simple - the first player can’t move, so the second player always wins. For the $2\times 1$ and $1\times 2$ games, only one player has a move to make, so they always win.

Let’s look at a few more games.

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | V | V | V | V | V | V | V | V | V |

| 2 | H | 2 | 2 | |||||||

| 3 | H | 2 | ||||||||

| 4 | H | |||||||||

| 5 | H | |||||||||

| 6 | H | |||||||||

| 7 | H | |||||||||

| 8 | H | |||||||||

| 9 | H | |||||||||

| 10 | H |

First off, any $n\times 1$ or $1\times n$ game handles exactly the same as a $2\times 1$.

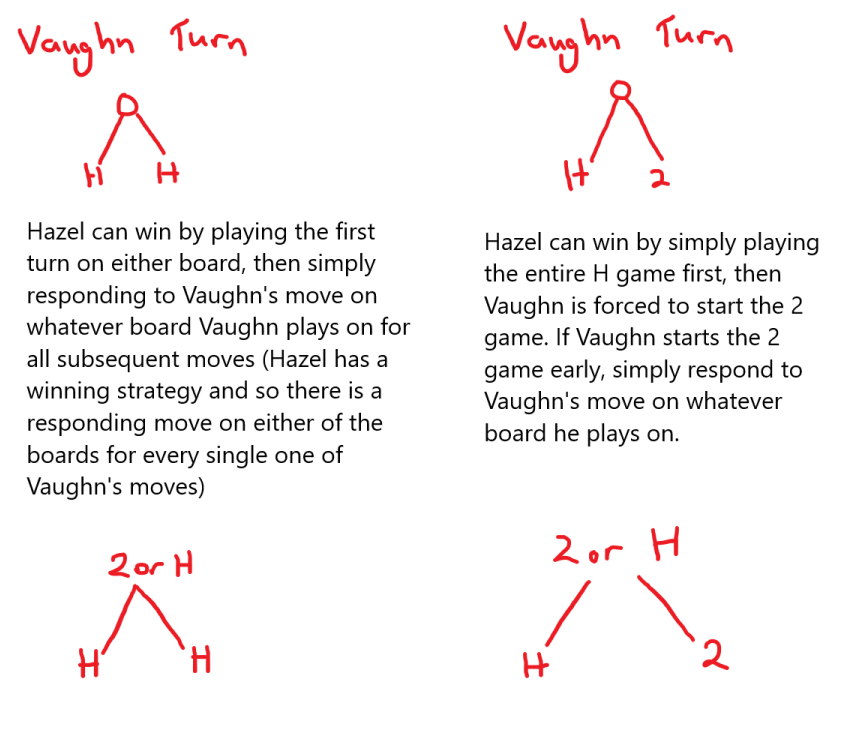

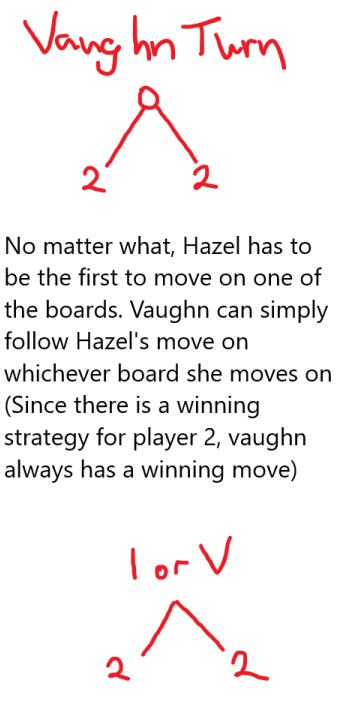

Next, for the $2\times 2$, note that whoever moves first will create two games that we’ve previously calculated they cannot win. Playing a game on two boards which individually the other player has a strategy to win is a loss for the starting player, because the responding player always has a winning move on both boards, provided they always play on the same board as the previous player’s move.

Additionally, for $3\times 2$ and $2\times 3$, note that the game will always become a combination of a $2\times 2$ and a $1\times 2$/$2\times 1$ game.

We’ve come up with the following two rules for cutting board (assuming that these 2 boards are the best the players can come up with). These rules also apply to Hazel when the outcomes are flipped.

There is one more rule that comes up when analysing $2\times 4$. Note that while Vaughn could split into $2\times 1$ and $2\times 3$, this would result in a loss (As our $2+H$ rule states). Instead, Vaughn can split the game into $2\times 2$ and $2\times 2$. Since both games are losing for the second player, Vaughn can just follow whatever board Hazel makes a move on, and Vaughn will always win the game (If Hazel makes a move on the first $2\times 2$ box, then Vaughn has a winning move on one of the resultant cutting boards).

With just these three rules in hand, we can actually fill the entire board:

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | V | V | V | V | V | V | V | V | V |

| 2 | H | 2 | 2 | V | V | V | V | V | V | V |

| 3 | H | 2 | 2 | V | V | V | V | V | V | V |

| 4 | H | H | H | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | V | V | V |

| 5 | H | H | H | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | V | V | V |

| 6 | H | H | H | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | V | V | V |

| 7 | H | H | H | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | V | V | V |

| 8 | H | H | H | H | H | H | H | 2 | 2 | 2 |

| 9 | H | H | H | H | H | H | H | 2 | 2 | 2 |

| 10 | H | H | H | H | H | H | H | 2 | 2 | 2 |

Hopefully by now you’re noticing the pattern. A proof left for the reader is why these 2s appear in boxes of size $2^k$. (Hint: Think about the first value in the row that can be a 2 rather than a H. What does it require in the values above it in the column? And what about the first value in the row that is a V, what needs to precede the V in the same row?)

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

import math

n, m = list(map(int, input().split()))

l2n, l2m = math.floor(math.log2(n)), math.floor(math.log2(m))

if l2n == l2m:

print("2nd Player")

elif l2n > l2m:

print("Vaughn")

else:

print("Hazel")

Cutting Board 2

Hint 1

If you’ve seen the solution for Cutting Board 1 - try a similar approach of mapping out the first few values in both dimensions. You should see a very different picture.

Hint 2

Notice that:

- Adding a cut will always take the game into $n$ copies of the same board, which will either be, $2$, V or H.

- Multiple games of $2$ are just $2$, Multiple games of V or H are just V or H.

As such, $2\times 2$, $2\times 3$, $2\times 5$ are essentially the same board, as far as this game is concerned. How is $2\times 4$ different?

Solution

As noted in the previous hint, let’s use the rules of combining boards to map out some smaller values:

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | V | V | V | V | V | V | V | V | V |

| 2 | H | 2 | 2 | V | 2 | V | 2 | V | V | V |

| 3 | H | 2 | 2 | V | 2 | V | 2 | V | V | V |

| 4 | H | H | H | 2 | H | 2 | H | V | 2 | 2 |

| 5 | H | 2 | 2 | V | 2 | V | 2 | V | V | V |

| 6 | H | H | H | 2 | H | 2 | H | V | 2 | 2 |

| 7 | H | 2 | 2 | V | 2 | V | 2 | V | V | V |

| 8 | H | H | H | H | H | H | H | 2 | H | H |

| 9 | H | H | H | 2 | H | 2 | H | V | 2 | 2 |

| 10 | H | H | H | 2 | H | 2 | H | V | 2 | 2 |

This table is a lot harder to decipher, but notice what the table looks like when I change the order of rows:

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | V | V | V | V | V | V | V | V | V |

| 2 | H | 2 | 2 | V | 2 | V | 2 | V | V | V |

| 3 | H | 2 | 2 | V | 2 | V | 2 | V | V | V |

| 5 | H | 2 | 2 | V | 2 | V | 2 | V | V | V |

| 7 | H | 2 | 2 | V | 2 | V | 2 | V | V | V |

| 4 | H | H | H | 2 | H | 2 | H | V | 2 | 2 |

| 6 | H | H | H | 2 | H | 2 | H | V | 2 | 2 |

| 9 | H | H | H | 2 | H | 2 | H | V | 2 | 2 |

| 10 | H | H | H | 2 | H | 2 | H | V | 2 | 2 |

| 8 | H | H | H | H | H | H | H | 2 | H | H |

We see strong bands of equal results. In a sense, all prime sized boards are equivalent, as are all boards of size 2 prime factors, and so on. Let’s continue this logic and permute the columns:

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 5 | 7 | 4 | 6 | 9 | 10 | 8 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | V | V | V | V | V | V | V | V | V |

| 2 | H | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | V | V | V | V | V |

| 3 | H | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | V | V | V | V | V |

| 5 | H | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | V | V | V | V | V |

| 7 | H | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | V | V | V | V | V |

| 4 | H | H | H | H | H | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | V |

| 6 | H | H | H | H | H | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | V |

| 9 | H | H | H | H | H | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | V |

| 10 | H | H | H | H | H | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | V |

| 8 | H | H | H | H | H | H | H | H | H | 2 |

In general, the best strategy seems to be: Cut out a prime factor of your board size, and you are left with multiple boards that will be best for you.

Note that

- If this produces winning boards for the opposite team, there was no way for you to win.

- If this produces winning boards for your team, then you can win simply by following whichever game your opponent plays first on.

- If this produces winning boards for the second player, then you can win simply by following whichever game your opponent plays first on.

Therefore the solution boils down to finding the number of prime factors a number has.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

MAX_N = int(2e6)

is_prime = [True] * (MAX_N+1)

is_prime[0] = False

is_prime[1] = False

for jump in range(2, MAX_N+1):

if not is_prime[jump]: continue

for pos in range(2*jump, MAX_N+1, jump):

is_prime[pos] = False

primes = [i for i, v in enumerate(is_prime) if v]

def n_prime_factors(v):

n_factors = 0

for p in primes:

while v % p == 0:

v //= p

n_factors += 1

return n_factors

n, m = list(map(int, input().split()))

n_factors = n_prime_factors(n)

m_factors = n_prime_factors(m)

if n_factors > m_factors:

print("Vaughn")

elif m_factors > n_factors:

print("Hazel")

else:

print("2nd Player")

Complexity: $\mathcal{O}(n)$

Divisors 0

Hint 1

Is there a formula we could be using that simplifies the sum of the first $n$ natural numbers?

If so, how would we change this formula for modulo?

Hint 2

Note that since we take the modulo of every individual value, the modulo-ed sequence repeats every $m$ values, so rather than computing the entire sequence, we can compute the sum of the first $m$ values and, excluding the final $n \% m$ bit of the sequence, we can simply count the number of repetitions.

Solution

As noted in the hint, the sequence repeats if we look at for example $n=14$, $m=4$.

\[1 + 2 + 3 + 4 + 5 + 6 + 7 + 8 + 9 + 10 + 11 + 12 + 13 + 14\]after modulo by 4 becomes

\[1 + 2 + 3 + 0 + 1 + 2 + 3 + 0 + 1 + 2 + 3 + 0 + 1 + 2\]Note that the $1 + 2 + 3 + 0$ sum is repeated a bunch of times, except for the final value $ + 1 + 2$.

Using the triangle number formula, the sum $1 + 2 + 3 + 0$ is equal to $\frac{3\times (3+1)}{2} = 6$, and this sequence is repeated $\lfloor \frac{14}{m} \rfloor = 3$ times.

So the total sum is equal to $3 \times 6 + 1 + 2$, however this final bit can be computed as $\frac{(n \% m)\times((n \% m) + 1)}{2} = 3$

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

n, m = list(map(int, input().split()))

triangle = (m * (m-1)) // 2

total = triangle * (n // m)

extra = n % m

total += (extra * (extra + 1)) // 2

print(total)

Divisors 1

Hint 1

Try to figure out a rule for what natural number $n$ will generate the value $a_b$ in the sequence.

Note that $1_a$ will always be generated by natural number $a$.

Hint 2

Hopefully you’ve figured out that number $a_b$ will be generated by the natural number $a \times b$.

As such, ordering by appearance in the sequence should just be ordering by $a\times b$, with some care needing to be taken when comparing $a_b$ with $c_d$ and $a\times b = c\times d$.

Solution

As mentioned in the hint, the value $a_b$ is generated by the natural number $a \times b$, and so ordering the individual values by the natural number which generates them should sort the sequence in order.

In the case where $a \times b = c \times d$, notice that the smaller divisor will always be included in the sequence first, so after comparing $a\times b$ against $c\times d$, we need only compare $a$ against $c$.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

nums = int(input())

v_and_p = list(map(lambda x: list(map(int, x.split("_"))), input().split()))

# Sort by (a*b, a) (And retain b so we can reconstruct the sequence)

sort_keys = list(map(lambda x: (x[0]*x[1], x[0], x[1]), v_and_p))

sort_keys.sort()

formatted = list(map(lambda x: f"{x[1]}_{x[2]}", sort_keys))

print(" ".join(formatted))

Divisors 2

Hint 1

Try to flip the problem on its head a bit and solve the case of counting how many 1s, 2s, 3s, etc. occur before the value you are looking for.

For example, 2 occurs 7 times before $3_5$.

Hint 2

For a natural number $n$, the value $a$ appears in the sequence before $n_1$ $\lfloor \frac{n}{a} \rfloor$ times.

This is all well and good for small $a$, but we can’t have a linear solution for this problem. You need to make use of the fact that for large $a$ (In particular, $a > \sqrt{n}$), the value of $\lfloor \frac{n}{a} \rfloor$ is always rather small (In particular $\lfloor \frac{n}{a} \rfloor \leq \sqrt{n}$)

Solution

To start with, let’s assume that we want to find the index of $n_1$ for some $n$ (The end of the sequence of divisors of $n$), since this will make our lives a bit easier.

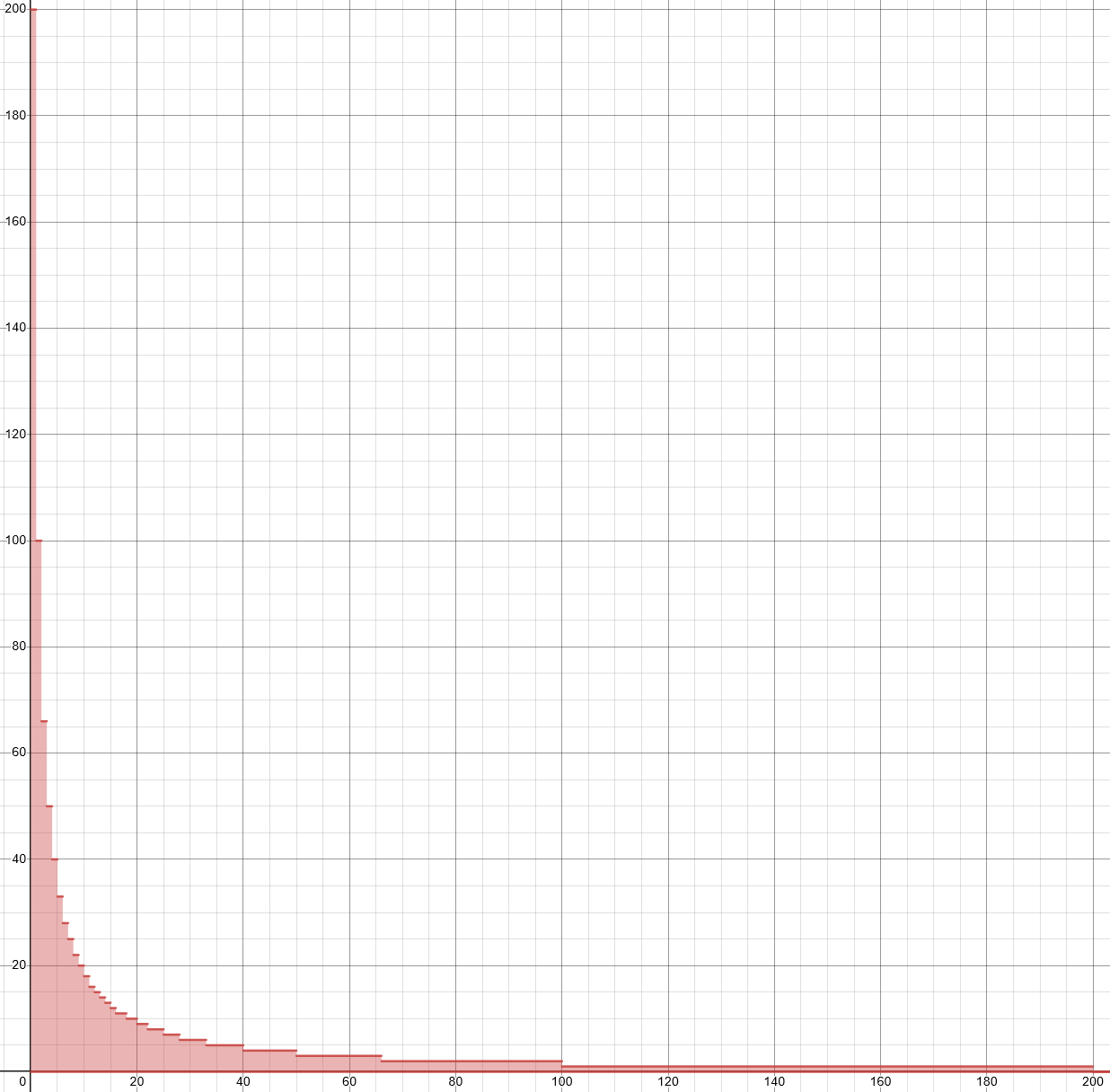

Notice that for any value $a$, $a$ will occur in the sequence before $n_1$ $\lfloor \frac{n}{a} \rfloor$ times. Let’s graph this for a large enough $n$:

This graph has a lot of large unique values for $a \leq \sqrt{n}$, and a few smaller common values for $a \geq \sqrt{n}$ (You can argue this via pidgeonhole principle - there are $\sqrt{n}$ possible values)

As such, we can count the first $\sqrt{n}$ values ourselves, and then count “sections” of the graph that are of equal size up to and including $\sqrt{n}$ in height.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

36

37

38

39

40

41

42

43

44

45

46

47

48

49

50

51

52

53

54

55

56

57

58

59

60

61

62

63

64

65

66

67

68

69

70

71

72

73

74

75

import math, sys

def val(inp):

special, noccurences = list(map(int, inp.split("_")))

# This occurs for number n*k.

nk = special * noccurences

# Find the index of (nk-1)_1 - Then we can just add the divisors of nk up until special.

nk -= 1

# Notice that nk // j can only be a few different values (nk, nk/2, nk/3 already is much smaller after 3 iterations)

# We can instead find, for i up until sqrt(n):

# All j such that nk//j = i

# Then simply compute nk//i for all remaining (small) i.

root = math.floor(math.sqrt(nk))

print("nk", nk, file=sys.stderr)

print("root", root, file=sys.stderr)

nums = 0 # We start at index 1.

for i in range(1, root+1):

# What j satisfy nk//j=i?

if i == 1:

nums += nk - nk//2

prev = nk // 2

continue

# Well, anything where i * j <= nk < (i+1)*j

# In other words, start at nk//(i+1)

# Ends when the previous barrier is hit

smallest_excl = nk // (i+1)

largest_incl = prev

prev = smallest_excl

nums += (largest_incl - smallest_excl) * i

print(f"nk // j = {i} for ({smallest_excl}, {largest_incl}]", file=sys.stderr)

# Now we need to find the rest

for i in range(1, root+1):

# Exclude the final entry for anything larger than special.

if nk // i <= root:

break

nums += nk // i

nk += 1

root = math.floor(math.sqrt(nk))

# Now we just need to add position for the final integer.

if special * special < nk:

# Simply count

for i in range(1, special + 1):

if nk % i == 0:

nums += 1

else:

# Count total

tot_turn = 0

for i in range(1, root+1):

if nk % i == 0:

tot_turn += 1

tot_turn *= 2

if root * root == nk:

tot_turn -= 1

for i in range(1, root+1):

if nk%i == 0 and nk // i > special:

tot_turn -= 1

elif nk%i == 0:

break

nums += tot_turn

if nk == 1:

# Previous doesn't work for base case

return 1

else:

return nums

print(val(input()))

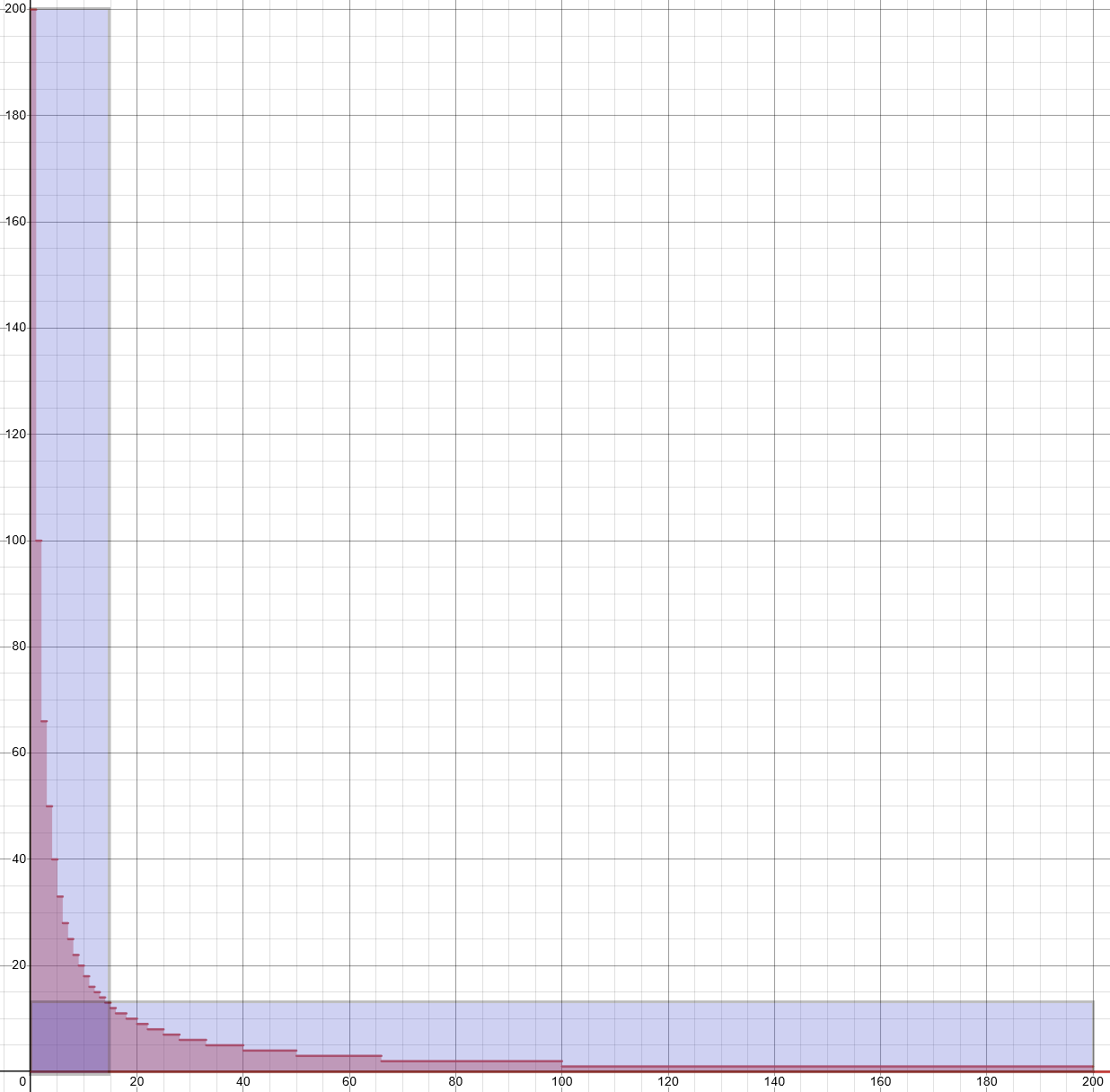

This however has a much more elegant solution, found by team de in the competition. Looking at the graph again, the graph is entirely the same when flipped along the axis $y=x$. So rather than counting the $\leq\sqrt{n}$ and $\geq \sqrt{n}$ cases separately, simply take the $\leq \sqrt{n}$ part of the graph, and double it.

This value then only double counts in the $\sqrt{n} \times \sqrt{n}$ box in the bottom left, which we can then subtract:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

36

37

# Courtesy of `de`.

a,b = map(int,input().split("_"))

n = a*b

m = int((n-1)**0.5)

# number of values for i <= sqrt(n-1)

tot = 0

for i in range(1,m+1):

tot += (n-1)//i

def numDivisor(i,n):

tot = 0

if i*i <= n:

for j in range(1,i+1):

if (n%j) == 0:

tot += 1

return tot

j = n/i

m = int(n**0.5)

numFacs = 0

smth = 0

for k in range(1,m+1):

if (n%k == 0):

numFacs += 1

if k < j:

smth += 1

numFacs *= 2

if m*m == n:

numFacs -= 1

return numFacs - smth

# double the area, subtract the square in the bottom left (m*m), and then add the divisors of just n up until a.

tot = 2*tot - m*m + numDivisor(a,n)

print(tot)

Divisors 3

A bit of a departure from all other problems in the contest, this problem asks you to approximate a sequence efficiently and effectively.

This problem ended up being a bit of a bad fit for a competition because a guarantee of maximum error is not the same as a practical guarantee of maximum error. Additionally, the accuracy and magnitude of the result was rather restrictive and made the problem a bit more annoying than it should have been.

Additionally, I didn’t do enough due diligence on checking my results, which made my initial solution incorrect (albeit accidentally accurate enough for the judge miraculously)

Hint 1

To solve the first boundary ( $\ln(n)$ ), you can solve this with a single line of code. (Moreso just a formula, than a line of code)

Also, I forgot to notice this in competition, but you’ll likely need an external package for extra decimal precision, like Pythons decimal package.

Hint 2

The problem bounds imply that $\sqrt{n}$ should somehow come into play. Is there a way we count the contributions of $\frac{1}{a}$ for $a <= \sqrt{n}$ differently from all other $\frac{1}{a}$?

Solution

First, let’s solve the first test set bound.

Notice that, just like in the previous problem, for an end value $n$, and $a \leq n$, the value $\frac{1}{a}$ will be in the sequence $\lfloor\frac{n}{a}\rfloor$ times.

Therefore we can over-estimate the contribution for $\frac{1}{a}$ in total as $\frac{1}{a} \times \frac{n}{a} = \frac{n}{a^2}$.

Summing over all $a$, we get the following sequence, which is a rather famous sequence:

\[\frac{n}{1^2} + \frac{n}{2^2} + \frac{n}{3^2} + \cdots + \frac{n}{n^2} = n (\frac{1}{1^2} + \frac{1}{2^2} + \frac{1}{3^2} + \cdots + \frac{1}{n^2}) \approx n \frac{\pi^2}{6}\]The error bound on the approximation of the sum of reciprocals is $\frac{1}{n}$, meaning that ignoring the error that removing the floor contributes, we are within $\frac{n}{n} = 1$ of the correct solution. However removing the floor can add as much as $\ln(n)$ to the result.

To solve the second test set bound, there was one intended solution, which didn’t end up actually ensuring the error bounds were met, and another solution that was found by team de. We’ll start with the semi-faulty solution.

Solution 1 - Modifying the test set 1 sequence.

Notice that the estimation error from $\frac{1}{a}\lfloor \frac{n}{a} \rfloor$ to $\frac{n}{a^2}$ is $\frac{n \% a}{a^2}$.

Let’s look at the full error expression for $n=20$:

\[\text{err} = \frac{0}{1^2} + \frac{0}{2^2} + \frac{2}{3^2} + \frac{0}{4^2} + \frac{0}{5^2} + \frac{2}{6^2} + \frac{6}{7^2} + \frac{4}{8^2} + \frac{2}{9^2} + \frac{0}{10^2} + \frac{9}{11^2} + \frac{8}{12^2} + \frac{7}{13^2} + \frac{6}{14^2} + \frac{5}{15^2} + \frac{4}{16^2} + \frac{3}{17^2} + \frac{2}{18^2} + \frac{1}{19^2}\]Notice that there are bands of rather well behaved fractions, for example from denominator 11 to 19. In general there will be an arithmetic progression on the numerators between the denominators of $\frac{n}{a+1}$ and $\frac{n}{a}$. Let’s try creating an estimator for these kinds of sequences.

\[R := \frac{a + bc}{x^2} + \frac{a+b(c-1)}{(x+1)^2} + \frac{a+b(c-2)}{(x+2)^2} + \cdots + \frac{a}{(x+c)^2}\]This sequence would be easier to resolve if the numerators increased with the denominators, rather than the opposite direction, so let’s do a manipulation.

\[(x + \frac{a}{b} + c) \times (\frac{1}{x^2} + \frac{1}{(x+1)^2} + \frac{1}{(x+2)^2} + \cdots + \frac{1}{(x+c)^2}) - \frac{R}{b} = \frac{x}{x^2} + \frac{x + 1}{(x+1)^2} + \frac{x + 2}{(x+2)^2} + \cdots + \frac{x+c}{(x+c)^2}\]Both sequences above have well known approximations, shown below:

\[\frac{1}{1^2} + \frac{1}{2^2} + \frac{1}{3^2} + \cdots + \frac{1}{n^2} = \frac{\pi^2}{6} - \frac{1}{n} - [0, \frac{1}{(n)(n+1)}]\] \[\frac{1}{1^2} + \frac{2}{2^2} + \frac{3}{3^2} + \cdots + \frac{n}{n^2} = \frac{1}{1} + \frac{1}{2} + \frac{1}{3} + \cdots + \frac{1}{n} = \ln(n) + \gamma + \frac{1}{2n} - [0, \frac{1}{8n^2}]\]where $\gamma$ is a constant. Substituting this into the equation above gives:

\[(x + \frac{a}{b} + c) \times (\frac{\pi^2}{6} - \frac{1}{x+c} - [0, \frac{1}{(x+c)(x+c+1)}] - \frac{\pi^2}{6} + \frac{1}{x-1} + [0, \frac{1}{(x-1)(x)}]) - \frac{R}{b} = \ln(x+c) + \gamma + \frac{1}{2(x+c)} - [0, \frac{1}{8(x+c)^2}] - \ln(x-1) - \gamma - \frac{1}{2(x-1)} + [0, \frac{1}{8(x-1)^2}]\] \[(x + \frac{a}{b} + c) \times (\frac{1}{x-1} - \frac{1}{x+c} + [-\frac{1}{(x+c)(x+c+1)}, \frac{1}{(x-1)(x)}]) - \frac{R}{b} = \ln(\frac{x+c}{x-1}) + \frac{1}{2(x+c)} - \frac{1}{2(x-1)} + [-\frac{1}{8(x+c)^2}, \frac{1}{8(x-1)^2}]\]Which solving for $R$ gives us

\[R = (xb + a + bc) \times (\frac{1}{x-1} - \frac{1}{x+c}) - b \times (\ln(\frac{x+c}{x-1}) + \frac{1}{2(x+c)} - \frac{1}{2(x-1)})\]with an error bound at most $\frac{xb + a + bc}{(x-1)(x)} + \frac{b}{8(x-1)^2}$.

Let’s use this estimate for the denominators $11$ through to $19$. This has $b=1$, $x=11$, $c=8$, $a=1$:

\[R = (11 + 1 + 8) \times (\frac{1}{10} - \frac{1}{19}) - (\ln(\frac{19}{10}) + \frac{1}{38} - \frac{1}{20})\]which gives about $0.07$ off of the actual solution

Choosing $d$ from $1$ up until $m := \lfloor \sqrt{n} \rfloor$ we can look at the denominator range $\frac{n}{d}$ down to $\frac{n}{d+1}$.

This has $b = d$, $c = \lfloor\frac{n}{d}\rfloor - \lfloor\frac{n}{d+1}\rfloor - 1$, $x = \lfloor\frac{n}{d+1}\rfloor$, and $a = n \% \lfloor \frac{n}{d} \rfloor$.

\[R = (d \lfloor \frac{n}{d+1} \rfloor + (n \% \lfloor \frac{n}{d} \rfloor ) + d \times (\lfloor\frac{n}{d}\rfloor - \lfloor\frac{n}{d+1}\rfloor - 1)) \times (\frac{1}{\lfloor\frac{n}{d+1}\rfloor -1} - \frac{1}{\lfloor\frac{n}{d}\rfloor - 1}) - d\times (\ln(\frac{\lfloor\frac{n}{d}\rfloor - 1}{\lfloor\frac{n}{d+1}\rfloor-1}) + \frac{1}{2(\lfloor\frac{n}{d}\rfloor - 1)} - \frac{1}{2(\lfloor\frac{n}{d+1}\rfloor-1)})\] \[R = (d \times (\lfloor\frac{n}{d}\rfloor - 1) + (n \% \lfloor \frac{n}{d} \rfloor )) \times \frac{\lfloor\frac{n}{d}\rfloor - \lfloor\frac{n}{d+1}\rfloor}{(\lfloor\frac{n}{d}\rfloor - 1) \times (\lfloor\frac{n}{d+1}\rfloor - 1)} - d\times (\ln(\frac{\lfloor\frac{n}{d}\rfloor - 1}{\lfloor\frac{n}{d+1}\rfloor-1}) + \frac{\lfloor\frac{n}{d+1}\rfloor - \lfloor\frac{n}{d}\rfloor}{2(\lfloor\frac{n}{d}\rfloor - 1)\times (\lfloor\frac{n}{d+1}\rfloor-1)})\] \[R = (n - d) \times \frac{\lfloor\frac{n}{d}\rfloor - \lfloor\frac{n}{d+1}\rfloor}{(\lfloor\frac{n}{d}\rfloor - 1) \times (\lfloor\frac{n}{d+1}\rfloor - 1)} - d\times (\ln(\frac{\lfloor\frac{n}{d}\rfloor - 1}{\lfloor\frac{n}{d+1}\rfloor-1}) + \frac{\lfloor\frac{n}{d+1}\rfloor - \lfloor\frac{n}{d}\rfloor}{2(\lfloor\frac{n}{d}\rfloor - 1)\times (\lfloor\frac{n}{d+1}\rfloor-1)})\]Although in practice I found

\[R = 1 - d \times \ln(\frac{d+1}{d})\]A relatively good and simple estimator for the above. (But the solution will use the lengthy approximation)

What is the error in this approximation? Well, there ends up being lots of cancellations in errors, since we are combining together lots of chained approximations, and so what was a positive error in the previous step now becomes the same negative error (this is not true for all error, for example some of the error in the harmonic approximation, but it is true for some).

Unless I’ve screwed something up (very possible) the total error ends up being a small factor of $\frac{1}{\sqrt{n}}$. This seems to atleast be true in practice.

For the values $\frac{n \% c}{c^2}$ for $c \leq \sqrt{n}$, we can just compute those manually.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

import sys

import math

from decimal import Decimal, getcontext

getcontext().prec = 50

n = int(input())

# Subtract 1 for the trail off

res = Decimal(n) * Decimal(math.pi) * Decimal(math.pi) / Decimal(6) - 1

print("Pretty good approximation:", res, file=sys.stderr)

ceil = min(n, int(1e6))

# Now, we need to reduce by a%d/d^2 for all d <= a.

for d in range(1, n // ceil):

d = Decimal(d)

smol = Decimal(n // (d + 1))

beeg = Decimal(n // d)

first_part = d * smol + (n % beeg) + d * (beeg - smol - 1)

second_part = Decimal(1) / Decimal(smol - 1) - Decimal(1) / Decimal(beeg - 1)

third_part = Decimal.ln((beeg - 1) / (smol - 1)) + Decimal(1) / (2 * (beeg - 1)) - Decimal(1) / (2 * (smol - 1))

reduction = first_part * second_part - d * third_part

# print(f"1/{n//d}^2 + ... + {n//(d+1)}/{n//(d+1)}^2 = {reduction}")

res -= reduction

# Below sqrt(a), we can manually subtract the value

for d in range(2, ceil):

res -= Decimal(n % d) / Decimal(d*d)

print("Better:", res, file=sys.stderr)

print(res)

Solution 2 - Other approximations

This solution was found by team de in competition.

Rather than sticking with the $\frac{n\pi^2}{6}$ approximation, this solution instead goes back to the original sequence and looks at it with a new viewpoint:

Let’s collect all of the $\frac{1}{1}s$, $\frac{1}{2}s$, and so on, in distinct columns, where the height of the column represents how many times that fraction is used.

We can sum the columns before and after $m = \lfloor \sqrt{n} \rfloor$ differently.

For those before $m$, we can simply find each column’s contribution by adding $a \times \lfloor\frac{n}{a}\rfloor$. For those after $m$, notice that $\lfloor \frac{n}{a} \rfloor$ will only take at most $m+1$ unique values (Since $\lfloor \frac{n}{m} \rfloor \leq m+1$), and in fact. This means that if, rather than summing by column, we instead sum by row, we’ll have only $m$ sets of values to compute, rather than $n-m$.

It’s worth noting that before $m$, we have $m$ distinct columns, and so after $m$, we have $m$ distinct rows (subject to off by one issues)

What do our rows of the graph look like? Well, using the previous image, every row (From column $m$ onwards), will be a sum of consecutive reciprocals up until some point. For example, for $n=9$, $m=3$, we have:

\[\frac{1}{3} +\] \[\frac{1}{3} + \frac{1}{4} +\] \[\frac{1}{3} + \frac{1}{4} + \frac{1}{5} + \frac{1}{6} + \frac{1}{7} + \frac{1}{8} + \frac{1}{9}.\]Now each of these rows we can use the approximation $\frac{1}{1} + \frac{1}{2} + \frac{1}{3} + \ldots + \frac{1}{n} = \ln(n) + \gamma + \frac{1}{2n} + \mathcal{O}(\frac{1}{n^2})$.

Applying this gives us:

\[\ln(\frac{3}{2}) + \frac{1}{6} - \frac{1}{4} + \mathcal{O}(\frac{1}{m^2}) +\] \[\ln(\frac{4}{2}) + \frac{1}{8} - \frac{1}{4} + \mathcal{O}(\frac{1}{m^2}) +\] \[\ln(\frac{9}{2}) + \frac{1}{18} - \frac{1}{4} + \mathcal{O}(\frac{1}{m^2})\]So we can use this to solve the problem with a total error bound of $\mathcal{O}(\frac{m}{m^2}) = \mathcal{O}(\frac{1}{m})$!

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

# Rephrased version of team `de`s solution.

from decimal import Decimal, getcontext

getcontext().prec = 50

n = int(input())

m = max(1,int(n**0.5))

m1 = n//m

total = Decimal("0")

# Handle the first m columns

for i in range(1, m+1):

total += Decimal(n//i)/Decimal(i)

# Handle the remaining m1 rows

for i in range(1, m1+1):

total += Decimal.ln(Decimal(n//i) / Decimal(m)) + Decimal(1) / Decimal(2 * (n//i)) - Decimal(1) / Decimal(2 * m)

print(total)

Lights 1

Hint 1

Simulating the problem takes $\mathcal{O}(n\ln(n))$ time. Too much - there actually aren’t many lights that will be turned on, and we can generate them in a neat sequence.

Hint 2

Consider a (faulty) proof that no light should be turned on. What is wrong with it, and what does this tell us about the solution?

Consider any light $n$. Take any factor of $n$, call it $a$. Note that $\frac{n}{a}$ will be another distinct factor of $n$ - This is true for all $a$ we could have chosen. Since this is the case (every factor has a unique pair), the total number of factors of $n$ is even. Therefore light $n$ is off.

Solution

The issue with the proof given in Hint 2, is that for square numbers, the “pairing” maps the square root of a number with itself. Take $36$ for example, the divisors $1, 2, 3$ are paired with $36, 18, 12$ respectively, but $6$ is its own pair.

In fact, square numbers are the only numbers for which the proof given in Hint 2 doesn’t work, for this very reason. So the problem really boils down to counting how many square numbers are less than $n$. We can do this easily by simply returning $\lfloor \sqrt{n} \rfloor$!

1

2

3

4

5

6

import math

n = int(input())

print(math.floor(math.sqrt(n)))

Lights 2

Hint 1

Note importantly that if Robot $a$ flicks a light switch, then Robot $a-1$ also flicks the same switch.

Hint 2

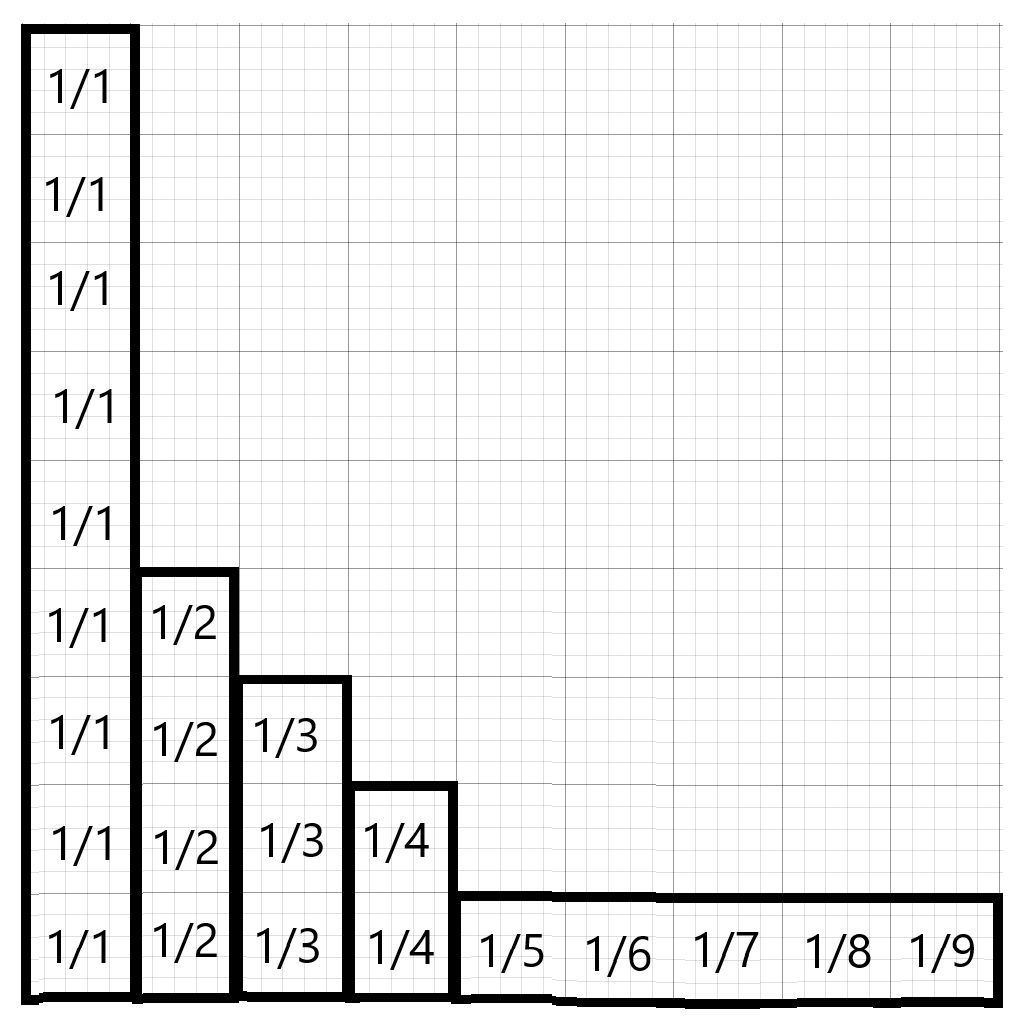

Consider the first $2^i$ lights. How many have been flicked once? twice? three times?

Solution

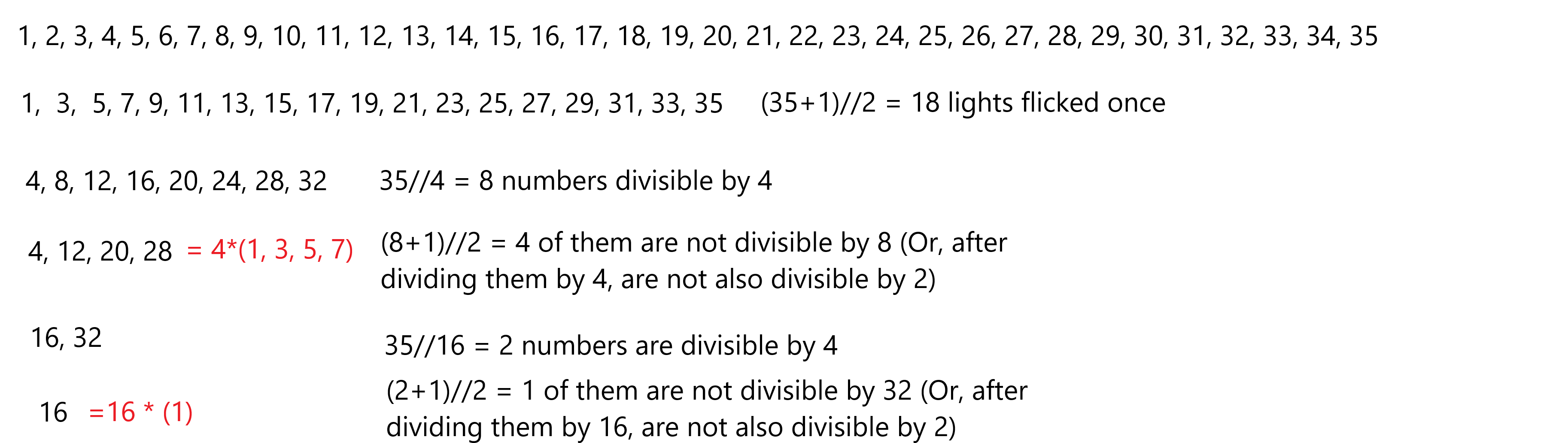

Using Hint 1, what we really need to find are the lights which are flicked on by Robot 1, but not Robot 2 (those that are flicked once), the lights which are flicked on by Robot 3, but not Robot 4 (those that are flicked thrice), and so on.

The lights that are flicked on by Robot 1, but not Robot 2 are those which are divisible by $2^0=1$, but are not divisible by $2^1=2$.

For the first $n$ lights, exactly $\lfloor \frac{n+1}{2} \rfloor$ of them will satisfy this rule.

The lights that are flicked on by Robot 3, but not Robot 4 are those which are divisible by $2^2=4$, but are not divisible by $2^3=8$. If we floor divide $n$ by $4$, and call this $m$, there are $m$ numbers divisible by $4$. Divide all these numbers by $4$. Now the question is simply how many of these are divisible by $2$, rather than divisible by $8$! So this is just the same as the first Robot question.

In general, the number of odd-flicked lights will be:

\[\lfloor \frac{n+1}{2} \rfloor + \lfloor \frac{\lfloor \frac{n}{4} \rfloor + 1}{2} \rfloor + \lfloor \frac{\lfloor \frac{n}{16} \rfloor + 1}{2} \rfloor + \lfloor \frac{\lfloor \frac{n}{64} \rfloor + 1}{2} \rfloor + \ldots\]Until this flooring starts giving 0 terms.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

n = int(input())

total = 0

cur_divisor = 1

while True:

div_by_divisor = n // cur_divisor

not_div_by_2 = (div_by_divisor+1)//2

if not_div_by_2 == 0:

break

total += not_div_by_2

cur_divisor *= 4

print(total)

Lights 3

Hint 1

Assuming you’ve solved Lights [I], this shouldn’t be too much of a stretch.

If a lighter $n$ is on in this configuration, what does it tell us about the divisors of $n$?

Hint 2

This problem statement counts the number of odd divisors of a number. For an odd number, how does this relate to the number of total divisors? For a number which has a prime factorisation including $2^i$, how does this relate to the number of total divisors?

Solution

One important tool we can use for this problem is the prime factorisation of a number. Take $12$ for example, it has a prime factorisation of $2^23^1$. Note that any divisor of 12 is created simply by setting the power of $2$ to be anything from $0, 1, 2$, and the power of $3$ to be anything from $0, 1$. ($1 = 2^03^0$, $6 = 2^13^1, \ldots$).

In general, if your prime factorisation is $a_1^{a_2}b_1^{b_2}c_1^{c_2}\cdots$, then your number has $(a_2+1)(b_2+1)(c_2+1)\cdots$ divisors, to account for all choices of the indicies.

Now, for odd numbers, any divisor is an odd divisor, so the same theory applies - only square numbers work.

But what about for evens? Take some number $n = 2^i3^j5^k$. This number has $(i+1)(j+1)(k+1)$ divisors, but the number of odd divisors is just the number of divisors where we picked the power of $2$ to be $2^0$.

Therefore the number of odd divisors of $n$ is $(j+1)(k+1)$. In other words, its the number of divisors of the odd number $3^j5^k$, which must be a square number.

So the only lights that should be on, are odd square numbers, and odd square numbers times a power of two.

Notice however, that since $2 \times 2$ is itself a square number, we can actually count all of the above numbers by simply counting all square numbers, and all square numbers times plain old 2. Take $2^3 \times 5^2$ for example, we can write this instead as $2 \times 10^2$.

We can count the number of squares, and the number of numbers which are two times a square simply with

\[\lfloor \sqrt{n} \rfloor + \lfloor \sqrt{\frac{n}{2}} \rfloor\]1

2

3

4

5

6

import math

n = int(input())

total = math.floor(math.sqrt(n)) + math.floor(math.sqrt(n//2))

print(total)

Lights 4

Hint 1

The logic used in Lights 3 around how many divisors a number has will remain useful here:

In general, if your prime factorisation is $a_1^{a_2}b_1^{b_2}c_1^{c_2}\cdots$, then your number has $(a_2+1)(b_2+1)(c_2+1)\cdots$ divisors.

Hint 2

This problem needs a rather sophisticated prime counting function.

Solution

Let’s use the rule given in Hint 1 to try to come up with a way of figuring out if a light is on.

Since the number of divisors is equal to $(a_2+1)(b_2+1)(c_2+1)\cdots$, the number of divisors will be prime only when:

- There is a single prime divisor of the number (Since $(a_2+1)(b_2+1)$ is already non-prime), and

- $a_2+1$ is prime.

In other words, the prime factorisation of $n$ must be $p^i$, where $i+1$ is prime.

Now, we could compute this linearly using a prime sieve, however we need to be a bit faster than this. There’s actually a batched way that we could solve this.

Let’s first counting the number of values before $n$ which are represented as $p^1$ - This is just the number of primes before $n$. Next, we’ll count the number of values before $n$ which are represented as $p^2$ - This is just the number of primes that appear before $\sqrt{n}$ (Since squaring the left side gives a number we are looking for, and squaring the right side gives $n$).

In general, if $\pi$ is the prime counting function ($\pi(n)$ = number of primes at or before $n$), then we need to compute

\[\pi(n) + \pi(n^{1/2}) + \pi(n^{1/4}) + \pi(n^{1/6}) + \pi(n^{1/10}) + \cdots\]Now we just need a fast prime counting function, luckily the wikipedia page for prime counting functions has some tools we can use to make a faster prime counting function, in particular following a link to The Meissel Lehmer Algorithm - you can see that there exists an optimised version that solves the problem in $\mathcal{O}(n^\frac{2}{3})$ time, however for our purposes we can just use some simple rules from the Meissel Lehmer algorithm and makes something sublinear.

The primary thing to note from the mention of the algorithm in the prime counting function page, and, the main page for the algorithm, is that for our purposes, picking $y = \sqrt{n}$ and $n = \pi(y)$, then computing $\pi(m) = \phi(m, n) + n - 1 - P_2(m, n)$ is easy, because $P_2(m, n)$ is 0.

So all that’s left is simply to implement the recursion of $\phi$ efficiently. We can use a sieve up to $10^6$ for fast computation for small numbers, and for larger results simply defer to recursion:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

36

37

38

39

40

41

42

43

import sys

import math

sys.setrecursionlimit(int(1e5))

n = int(input())

# pi(n) + pi(sqrt(n)) + pi(n^1/4) + ...

prime_limit = int(3e6)

is_prime = [True] * (prime_limit+1)

pi = [0] * (prime_limit+1)

primes = []

is_prime[0] = False

is_prime[1] = False

for x in range(2, prime_limit+1):

pi[x] = pi[x-1]

if not is_prime[x]: continue

pi[x] += 1

primes.append(x)

for pos in range(2*x, prime_limit+1, x):

is_prime[pos] = False

def phi(m, n):

if m <= prime_limit and pi[m] <= n:

return 1

if n == 0:

return math.floor(m)

return phi(m, n-1) - phi(m//primes[n-1], n-1)

def fast_prime(n):

m = n

y = math.floor(math.sqrt(m))

n = pi[y]

return phi(m, n) + n - 1

total = 0

for x in range(1, math.floor(math.log2(n)) + 1):

if is_prime[x+1]:

total += math.floor(fast_prime(math.floor(math.pow(n, 1/x))))

print(x, total, file=sys.stderr)

print(total)

One other optimisation that can be made is noticing that the recursion tree is often quite long with a lot of small branches (At some stage if dividing $n$ by any large prime $p$ will give you the base case, then we can use binary search to find the first prime which won’t hit the base case)

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

36

37

38

39

40

41

42

43

44

45

46

47

48

49

50

51

52

53

54

55

56

57

58

import sys

import math

sys.setrecursionlimit(int(1e5))

n = int(input())

# pi(n) + pi(sqrt(n)) + pi(n^1/4) + ...

prime_limit = int(3e6)

is_prime = [True] * (prime_limit+1)

pi = [0] * (prime_limit+1)

primes = []

is_prime[0] = False

is_prime[1] = False

for x in range(2, prime_limit+1):

pi[x] = pi[x-1]

if not is_prime[x]: continue

pi[x] += 1

primes.append(x)

for pos in range(2*x, prime_limit+1, x):

is_prime[pos] = False

def phi(m, n):

if m <= prime_limit and pi[m] <= n:

return 1

if n == 0:

return math.floor(m)

# Try binary searching through a bunch of the easy to solve stuff.

if n > 50 and m > prime_limit and m//primes[n-1] <= prime_limit and 2*pi[m//primes[n-1]] <= n-1:

hi = n

lo = 10

while hi - lo > 2:

mid = (hi + lo) // 2

new_m = m//primes[mid]

if new_m <= prime_limit and 2*pi[new_m] <= mid:

# We can go lower

hi = mid + 1

else:

# We can't go this low

lo = mid + 1

# Skip from n to mid in n-mid steps, since all deductions will just be -1.

return phi(m, mid) - (n-mid)

return phi(m, n-1) - phi(m//primes[n-1], n-1)

def fast_prime(n):

m = n

y = math.floor(math.sqrt(m))

n = pi[y]

return phi(m, n) + n - 1

total = 0

for x in range(1, math.floor(math.log2(n)) + 1):

if is_prime[x+1]:

total += math.floor(fast_prime(math.floor(math.pow(n, 1/x))))

print(x, total, file=sys.stderr)

print(total)

Misc 0

Hint 1

It might be first good to simplify the fraction given to you, and seeing what you can do with this information.

Hint 2

If the simplified fraction of the problem is $\frac{c}{d}$, then at every integer time you’ll actually see all values of $\frac{x}{d}$ around the circle. So what does $d$ tell us about whether we hit the other side?

Solution

To quickly prove the result of Hint 2, notice that if the simplified fraction is $\frac{c}{d}$, then we know that $c$ and $d$ are coprime, in other words $\text{gcd}(c, d) = 1$. Then there exists some values $x$ and $y$ such that $cx + dy = 1$. Consider where we will be after $x$ seconds. We’ll be at $\frac{cx}{d} = \frac{1 - dy}{d} = \frac{1}{d} - y = \frac{1}{d}$ rotation around the circle (If $x$ is negative, just keep adding $d$ seconds until it is positive and you’ll get the same result). So in $x$ seconds we can move $\frac{1}{d}$ around the circle, and so in $x\times a$ seconds we can move to $\frac{a}{d}$ around the circle for any integer $a$. Hopefully it is relatively clear that for a simplified fraction of $\frac{c}{d}$, any rotation not expressible as $\frac{a}{d}$ is not possible after an integer amount of seconds.

Now, all we need to determine is whether we hit the opposite side of the circle, $\frac{1}{2}$. This is only possible (and always possible) if $\frac{1}{2}$ is expressible as $\frac{a}{d}$ for some $a$.

Which hopefully you can see is always possible if $d$ is divisible by $2$.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

a, b = list(map(int, input().split()))

# Simple lcm work.

for x in range(2, min(a, b)):

while a % x == 0 and b % x == 0:

a //= x

b //= x

# 1/b is the jump size.

if b % 2 == 0:

print("Other axis!")

else:

print("Free!")

Misc 1

Hint 1

This problem is best viewed through the lens of recursion. Your recursion will likely need to look back at all previous values (I.E., parens(4) can be written as some combination of parens(3), parens(2), parens(1), parens(0))

Hint 2

Think about all possible parenthesis strings of containing $n$ closed parentheses. Each of these valid strings must start with an open parenthesis, which is closed at some point. What do I know about the strings in between these two parentheses, as well as after these two parentheses?

Solution

To answer Hint 2, the inside string and following string must both represent valid parenthesis strings!

Therefore, we can construct a valid parenthesis string of length $n$ by deciding:

- How many parenthesis will occur inside the first closed parenthesis, call it $a$

- What is a valid parenthesis string of length $a$ to use inside

- What is a valid parenthesis string of length $n-a-1$ to use outside

And this informs our recursive counting function. To compute parens(n), simply:

- Iterate for all $a$ from 0 to $n-1$

- Compute

parens(a) * parens(n-1-a) - Add to the total and return the sum.

We just need to add some modular arithmetic to the solution and we are done:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

import sys

sys.setrecursionlimit(int(1e5))

MOD = int(1e9+7)

n = int(input())

DP = [None] * int(1e3 + 5)

# How many parens patterns are there?

def parens(n):

if DP[n] is not None:

return DP[n]

if n <= 1:

return 1

total = 0

for a in range(n):

# There are a parens in the first pattern

total += (parens(a) * parens(n-a-1)) % MOD

total %= MOD

DP[n] = total

return total

print(parens(n))

Note - These are called the Catalan Numbers, and I was going to include many more problems featuring them originally. If you’re looking for a beautifully unique proof, look at Betrand’s Ballot Theorem, a generalisation of the Catalan numbers.

Misc 2

I guess I wasn’t thinking too much when I wrote this problem since it includes a data structure, but I think I count trees as more math than data structure, they are simply too fundamental :)

Hint 1

Try to think about the contributions on the left and right side of the removed edge separately (as well as that contributed by the edge itself separately). These three values when combined give you the answer.

Hint 2

The easiest of the three values to calculate is the amount contributed by the removed road itself.